The 21st century has witnessed a shift in dominance from oil to microchips. Today, political, economic, and military power is intricately tied to these semiconductors. Mastery over semiconductor Global Value Chains (GVCs) has become a bone of contention between the United States (US) and China in technological competition. This US-China chip rivalry, which can become a blessing in disguise for Pakistan, presents significant opportunities for the country. Pakistan's cheap labour positions it as a key player within the chip industry, particularly in collaboration with these global leaders. This underscores the potential benefits for Pakistan in the US-China chip rivalry.

Chips are produced through GVCs, and the stages of the production process are spread among firms in different states. The supply chain begins with “fabless” chip makers in the US, who design the architecture of chips using “Electronic Design Automation” software. Its chip designers then outsource fabrication to “foundries” in Taiwan, South Korea, or Japan.

The Chinese semiconductor industry still lags far behind the other global chip competitors. According to Chris Miller in his book Chip War: The Fight for the World's Most Critical Technology, China spends more money importing microchips than oil. 95% of the chips China uses are designed by the US. Hence, it has been identified as a significant vulnerability of China's long-term ambitions. Amidst this context, President Xi launched an inward-looking state capitalism strategy prioritising Chinese firms over foreign firms to achieve self-sufficiency under the “Made in China 2025” plan and the 14th five-year plan for technology independence.

The US has intensified its competition with China in the chip industry by signing the “CHIPS and Science Act of 2022,” a comprehensive legislation to boost domestic chip production and research. The act includes provisions for a US$52.7 billion investment over five years to revitalise semiconductor production in the US, thereby reducing its dependence on foreign chip manufacturers. This significant move can reshape the global chip industry and directly affect the US-China chip rivalry. Furthermore, the US Department of Commerce issued new export controls to prevent China from accessing chips made with US equipment, areas where US technology is critical and irreplaceable, to slow down China’s military and technological advances. This competition was further intensified when Biden broadened the scope from bilateral to multilateral by proposing the “Chip-4 Alliance” to integrate the chip-related policies among chip-producing states against China. Beijing retaliated by banning the export of crucial rare elements for manufacturing chips, namely germanium and gallium. China produces 60% of the world's germanium and 98% of the world's gallium.

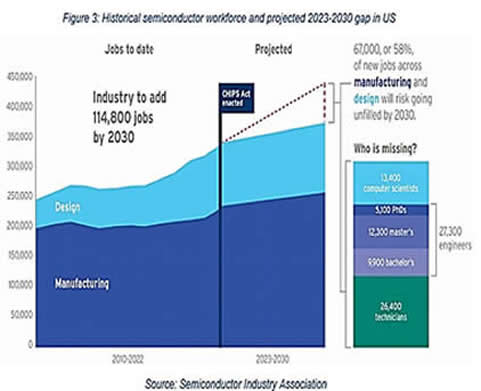

While the US and China are pouring billions into achieving self-reliance in the chip industry, the looming challenge of insufficient skilled labour is projected to be a significant hurdle in the coming years. The Semiconductor Industry Association anticipates that the US is expected to witness a growth in the semiconductor workforce from 345,000 jobs to an estimated 460,000 by 2030, marking a 30% increase. However, 58% of these expected new positions are at risk of remaining unfilled with the current degree completion rates. Similarly, the China Center for Information Industry Development think tank and the China Semiconductor Industry Association jointly published a white paper that projected a workforce deficit of 200,000 professionals in the chip industry. This is a particularly significant opportunity given Pakistan's nascent stage in the semiconductor space.

With its abundant, low-cost labour, Pakistan holds immense potential to emerge as a critical player in the chip industry. Drawing parallels, it's crucial to note that South Korea’s ascent as a chip-producing state was mainly due to its low-cost and skilled labour, which played a pivotal role in its chip industry. However, the question arises whether Pakistan possesses skilled labour in the chip sector.

Local universities in Pakistan need more highly trained faculty and academic resources in specialised domains such as micro and nano-electronics IC design. The chip sector in Pakistan comprises only a dozen companies, employing less than a thousand specialised engineers. Though Pakistan has surplus human capital, with 25,000 engineers graduating annually and further training, these engineers have the potential to become integral contributors to US and Chinese firms, filling the critical workforce void.

Pakistan has a minimal history in the chip industry due to its capital-intensive nature. Establishing a state-of-the-art semiconductor fabrication facility necessitates significant investment, ranging from US$2-20 billion - typically taking 6-8 years per industry estimates to achieve profitability. Therefore, the financial investment required at the fabrication stage is a formidable challenge for Pakistan.

Chip design requires software development and engineering proficiency, which could be more financially viable. In this context, emphasising chip design with outsourcing manufacturing would prove beneficial in the long run.

Although Pakistan does have a few companies that design chips (Table 01), they are in their early stages. The support of expat-led initiatives, such as Aql-Tech Solutions, which closely collaborates with a leading-edge RISC-V-based processor core IP provider company in the US, is significant in igniting progress. Pakistan needs to enhance such efforts by leveraging the expertise of expats to provide training and facilitate business development within the country.

Utilising the triple helix model, the Special Technology Zones Authority (STZA) is instrumental in fostering a conducive ecosystem for the chip industry, promoting collaboration among academia, industry, and government. Additionally, STZA, leveraging government-to-government partnerships, is collaborating with China to devise a multi-pronged strategy for chip design services.

Furthermore, through the Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC), Pakistan needs to incentivise foreign firms, particularly from China, to establish chip design centres. China's move to replace Western chips with its own RISC-V architecture presents an opportunity for Pakistan, akin to India's role in Y2K, that wouldn’t require much physical facility but skilled human resources.

Beyond chip design services, Captain (Retd.) Muhammad Mahmood, Additional Secretary of the IT and Telecommunication Division, said that considering Pakistan's economic constraints and limited trained engineers, an incremental approach could be more viable, beginning with testing and packaging.

Recognising that only some countries can independently perform all roles in the semiconductor GVCs, China would need to collaborate with friendly nations to achieve competitiveness. Pakistan stands as a promising potential partner. During PM Imran Khan's official visit to China, meetings with China's leading technological companies were held. By leveraging Pakistan's low-cost workforce, China could focus on higher-value segments of GVCs, underscoring the strategic importance of this collaboration.

In conclusion, to capitalise on the US-China chip competition, Pakistan needs to amplify its efforts in workforce training and specialised programmes, support entrepreneurship and startups, and, most importantly, collaborate with global chip leaders. The global chip market is projected to grow from $600 billion in 2023 to over $1 trillion by 2030 – Pakistan should aim to secure approximately US$5 billion by 2030.